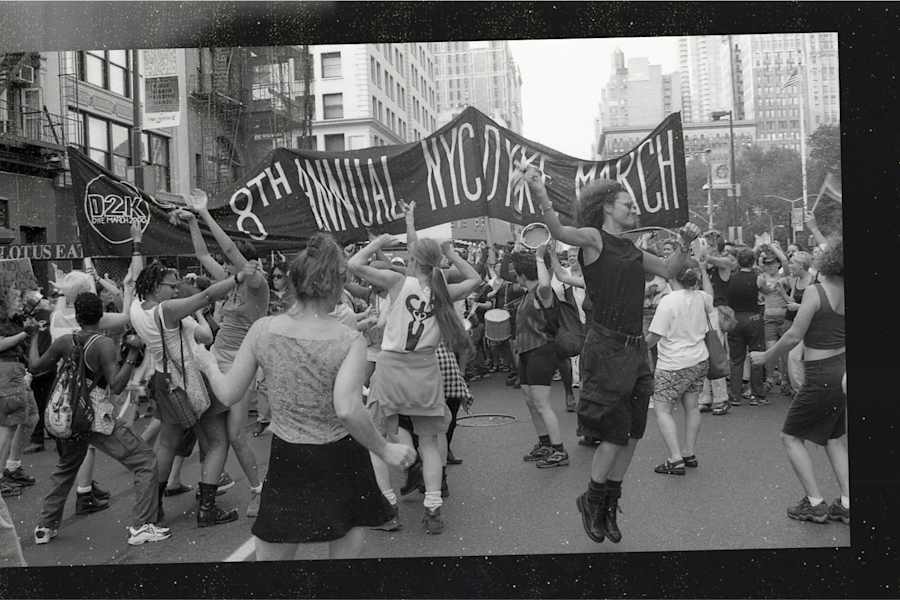

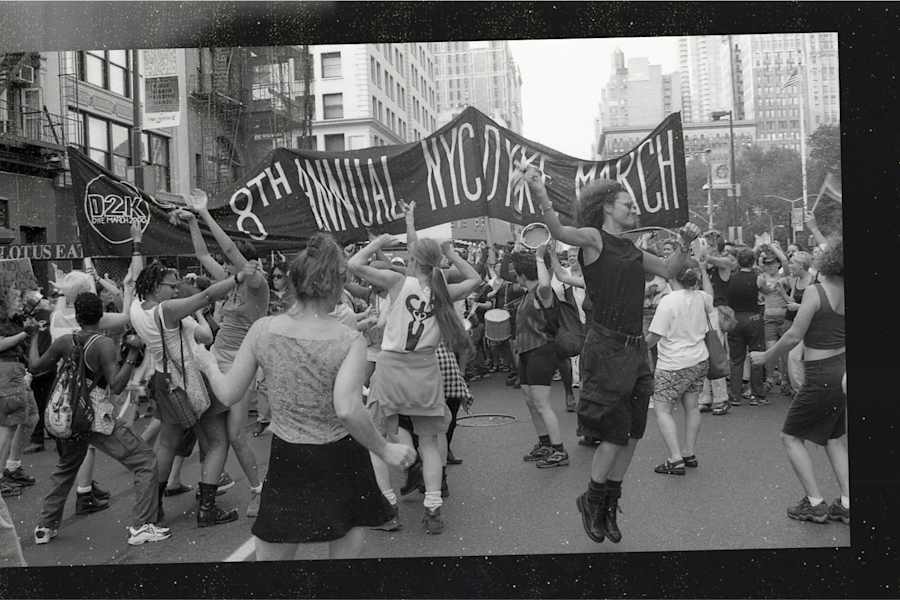

The New York City Dyke March, Then and Now

“[Dyke] means fuck you, in a really nice, inclusive way.”

Scan to download

There are as many ways as there are reasons to “flag” — the queer practice of signaling sexual availability through dress and style.

On February 13, 2023, Feeld hosted an event with Susan Alexandra in New York City. Guests collaborated with the brand to create their own accessories spelling out their desires and meeting like-minded people. In honor of the event, Feeld is looking back at the rich histories of queer flagging.

Black is for S&M. Red is for fisting. Light blue is for oral sex, dark blue for anal. Where the color shows up is just as important: on the left indicates topping or giving, right is for bottoming and receiving.

The hanky code, used predominantly by gay men in the 1970s and 80s, has become a legendary part of LGBTQ+ lore. In the 1980 film Cruising, an undercover cop (Al Pacino) investigating a serial killer in New York City’s leather scene has the code explained to him by a shopkeeper: put a bandana in your back pocket, and the color and position would indicate which sexual acts you were interested in giving to or receiving from other men. It went as mainstream as the sex lives of queer people could go in the era, inspiring similar acts of “flagging” in other sexual communities.

Queer histories are filled with stories of creativity, secret languages, and yes, sexual liberation. When fearing stigma, prejudice, and threats to physical safety from society at large, queer people have found subtle ways to flag their sexual availability to potential partners.

Like so many histories forced into the margins, the origins of flagging are ambiguous or disputed. One popular theory states that hanky flagging started during the Gold Rush in nineteenth-century San Francisco. Men went to strike it rich, and women and children were largely absent. According to historians, we know that gay relationships were common, if not outright accepted. Some theorize that during square dances, when available men vastly outnumbered women, men would wear blue bandanas to indicate they’d take the leading role, while red bandanas signified men that were willing to follow.

Modern iterations of the hanky code took off in the early 1970s. Some credit an article in The Village Voice which jokingly suggested that gay men use hankies to signal whether they were a top or a bottom. Others say that the code started in San Francisco in 1972 when Alan Selby, co-owner of S&M shop Leather ‘n’ Things, accidentally received a double order from their bandana supplier. Selby, known as “the Mayor of Folsom Street,” claims he created the code to help sell surplus bandanas.

Trying to find a definitive guide to the hanky code is tricky. The underground nature of the code meant that it changed by location and community. Sex shops looking to move stock printed their own guides, as did gay bars, bookstores, and bandana manufacturers. One archived pamphlet shared from The Boston Eagle, the iconic gay bar which shuttered its doors during the pandemic after 40 years in business, lists their hanky code with different meanings assigned to gold, green, lime, lemon, yellow, mustard, and peach. One has to wonder how these colors translated under the dim lights of a dark bar, and it’s been theorized that after a certain point, the hankies were used as conversation starters rather than a useful practical guide.

In 1984, legendary lesbian magazine On Our Backs included an adapted hanky code for women written by Pat Califia and Gayle Rubin, with colors indicating “is menstruating” or “breast fondler.” The magazine sold silk hankies in 18 colors by mail order.

Nails and nail polish have long been ways that lesbians and queer women have signaled to each other, especially amongst femmes who have experienced invisibility and erasure within the community. The “femme-icure” is the informal name given to that ubiquitous queer manicure featuring long nails on every finger save for the middle and pointer finger, leaving them available for sex. Kinsey Clarke, writing for Flare magazine about how keeping her nails long on every finger is its own form of flagging, different from the white lesbian mainstream: “Long acrylics made me feel like a cat with its claws extended — a femme fatale[...] for me, getting acrylics feels like confirmation of Black lesbian femininity.”

In the early 2010s, efforts were made to combine manicures with the history of queer flagging. Femme-flagging, also known as finger-flagging, involved painting one or two nails a different color to signify interest in sexual activities, similar to how the hanky code was used. Zines and pamphlets of the 80s were replaced with blogs and Tumblr accounts chronicling the ever-evolving code. The online nature of communication meant that the trend both moved quickly and was regionally dispersed, and little evidence is available to show whether it was actually useful for hooking up. Soon, “accent nails” became a trend among straight people, and the queer meanings were quickly replaced by heteronormative signifiers. In a roundtable with manicurists for Racked, one nail artist theorizes that accent nails rose in popularity because “women might be subconsciously trying to get their boyfriend or their love interest to put a ring on it,” while another states, “the accent nail started because women usually wear wedding rings on their ring finger.” Still, finger-flagging served as a short-lived form of expression among women who wanted to assert their femme identity while claiming their spot in the larger queer community.

For many LGBTQ+ people, it’s easier and safer to be publicly out today than it was in the 1970s. People across the spectrum of sexuality have more avenues to pursue kinks, group sex, and other sexual pursuits. Flagging events are still held that pay homage to the colorful histories of queer communities.

“[Dyke] means fuck you, in a really nice, inclusive way.”

Reflections from Feeld’s CEO on how Pride can be as much of a practice and a protest as it is a party.